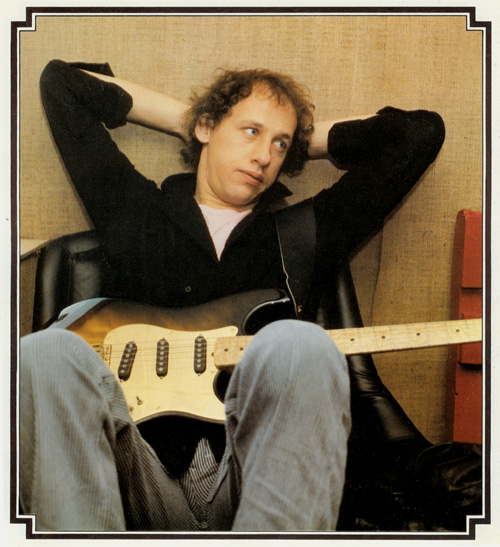

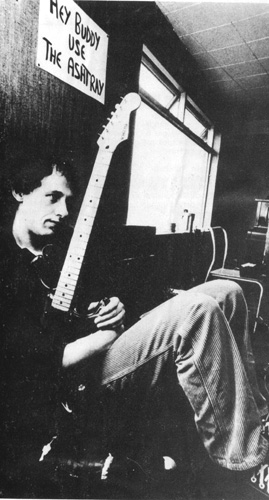

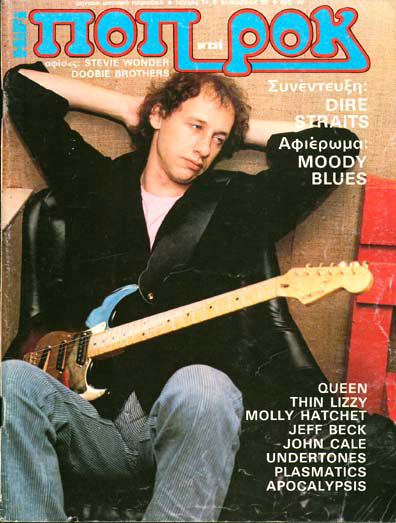

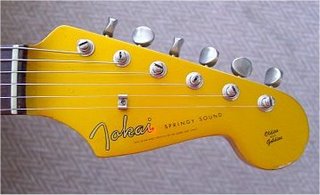

Mark Knopfler’s stolen sunburst Schecter Strat of Tunnel of Love

In 1980 Mark Knopfler bought some Schecter guitars (probably 4 Strats and a Telecaster) at Rudy’s Music Stop in New York. These were two red Strats (see my article about these here), one blue Strat, a black Telecaster, and a wonderful sunburst Strat. The last was the guitar that was played on the song Tunnel of Love on the Making Movies album. It seems he liked especially this one very much, he even said in an interview that it was possibly the best sounding guitar he ever had (however, this is something he used to say rather often about the latest guitar he got 😉 ).

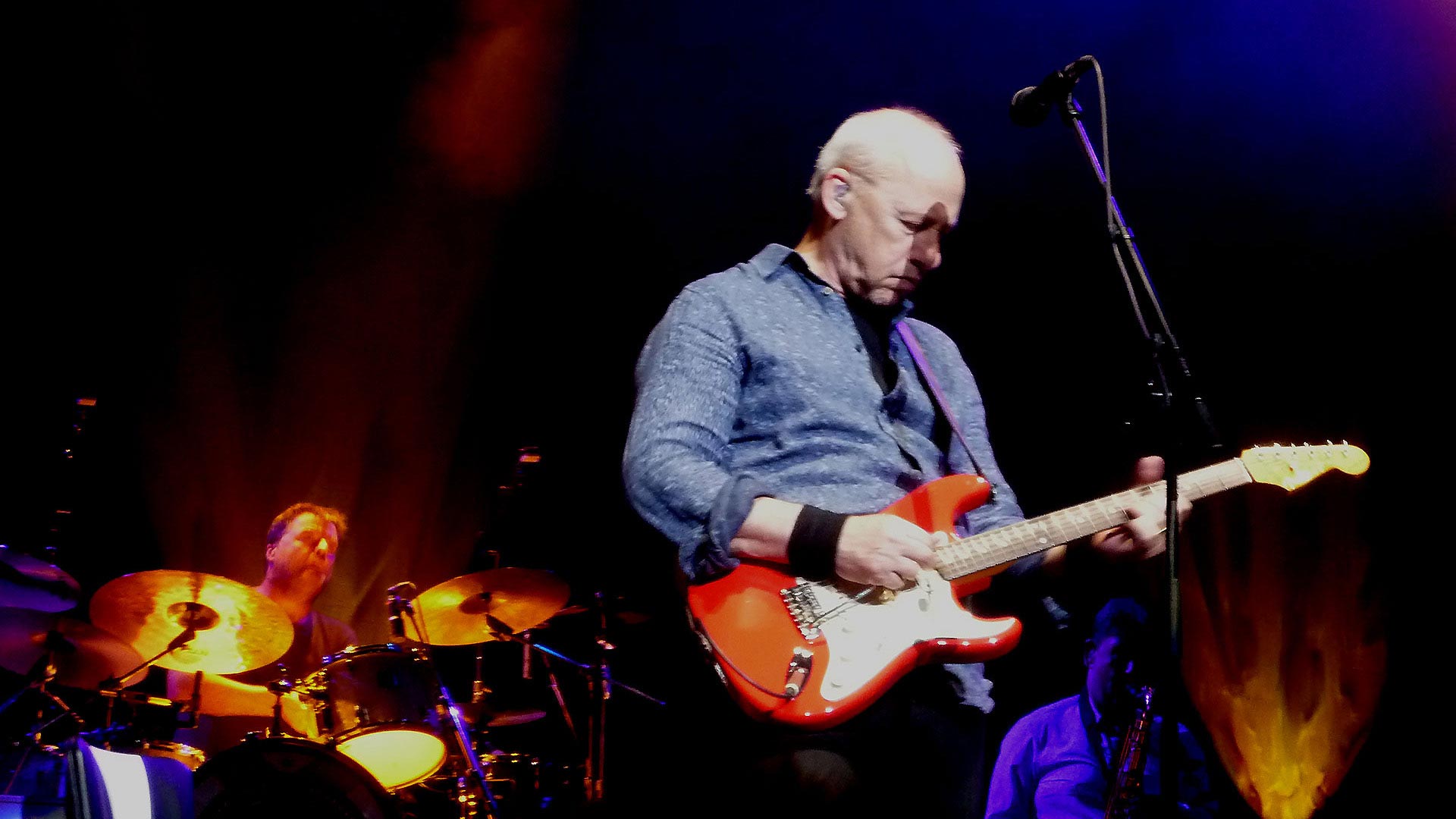

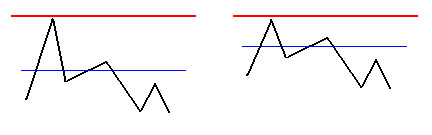

Unfortunately this guitar was stolen soon after the recording of Making Movies (if I remember correctly out of the car in Deptford, possibly after a rehearsal). This was some time before the first gig of the Making Movies tour because on this tour he played another sunburst Schecter Strat that he bought as a direct replacement for the stolen one. Both were similar, had probably the same pick-ups and the same basic features. Some differences that make both easy to distinguish on pictures are the dot markers (the first one had them while the second one was without) and the location of the output jack (the first had the normal Strat type recessed output jack, the second one had it on the body side, just like a Telecaster).

There are not too many details that are known about the stolen Schecter. The pick-ups were most likely Schecter F500Ts (quarter inch alnico magnets, the T stands for tapped coil), just like in the replacement guitar. According to Tom Anderson (former employee at Schecter who now builds his own guitars) the body of the sunburst Strat was birch (unfortunately we don’t know of which of the two sunburst Strats). The neck was beautifully figured bird’s eye maple.

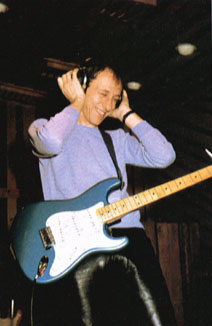

As he did not have it for a long time, there is only a small number of pictures of this guitar which all seem to be from the same photo session. To me this guitar looked incredibly cool, I love the two-tone sunburst which looks for some reason much better than on the replacement Strat. Below you can see all pictures I have of this guitar.