Understanding songs – chords and structure analysis of True love will never fade

Have a look at the following chords, these are all chords for the song True Love Will never Fade, the opener of Mark Knopfler’s latest album Kill to get crimson. Each chord is played for one bar:

C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C C F F C C Dm G C C F F C C Dm G F G C C F F C C Dm G C C F F C C Dm G C Dm G C Am F G F G C F Dm G C C F F C C Dm G C C F F C C Dm G C C F F C C Dm G C Dm G C Am F G F G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C C F F C C Dm G C C F F C C Dm G F G C C F F C C Dm G C C F F C C Dm G C Dm G C Am F G F G C F Dm G C C F F C C Dm G C C F F C C Dm C C F F C C Dm G C Dm G C Am F G F G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G C F Dm G

Theoretically it is no problem to play the song from this list of chords, you simply have to follow the list and try not to get lost 😉

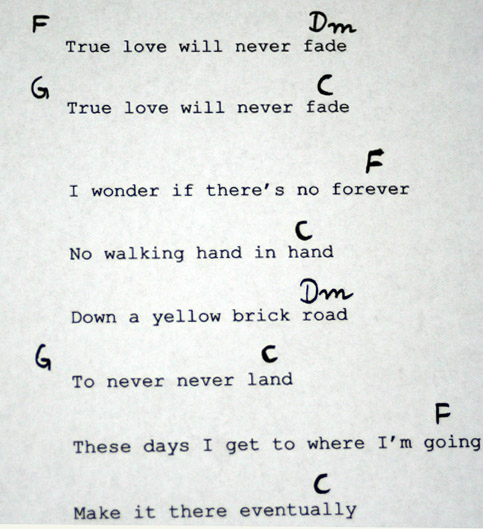

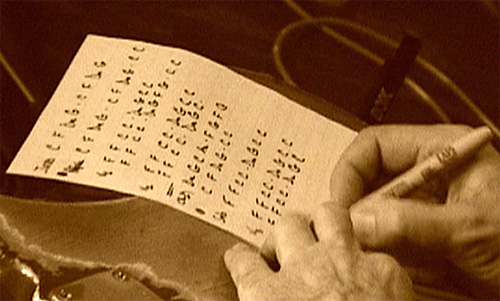

One way to avoid getting lost is writing the chords next to the corresponding words of the lyrics, something that is common among singers who accompany themselves. You surely have seen this approach, it might look like this:

Finding structure

The solution above is common but not ideal because it does not reflect any structure.

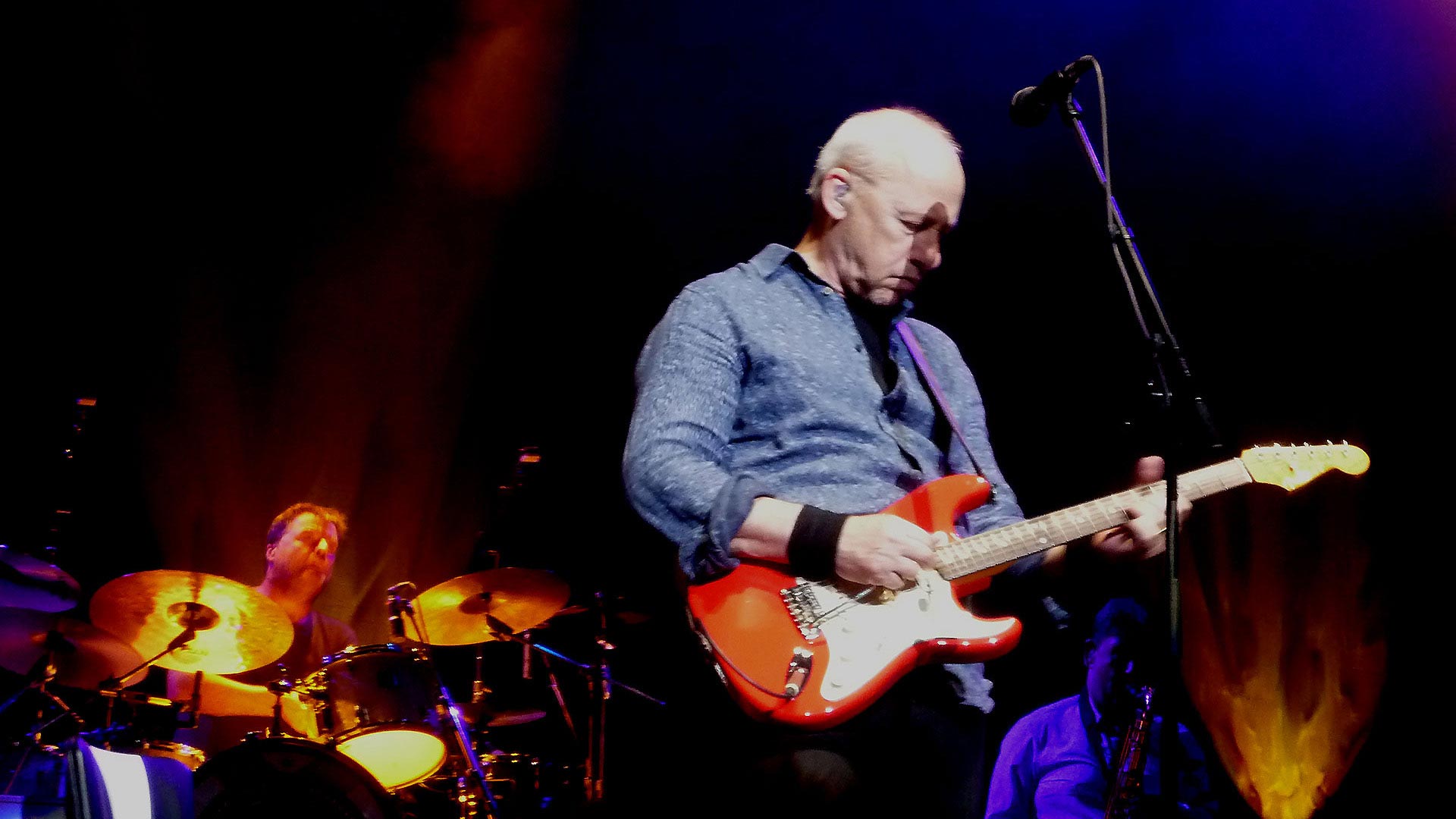

You might ask yourself how you can play such a song without a paper, like professional musicians do on stage? How can you learn a list of 126 chords by heart?

The answer is easy: you need to be aware of its structure, of the patterns and logic it is built up with. Without structure, understanding is not possible. Without understanding, learning and remembering is extremely difficult. It is similar to understanding a huge mixing desk: you might wonder how someone knows what to do with so many knobs and controls, there are actually hundreds of them. But when you have a closer look, you will see that there are several channel strips that all have an identical set of controls. And the controls of each channel strip are structered again in e.g. the EQ section, the aux controls for effect sends, the monitor section, and so on. As soon as you understand it, the number of controls is no problem anymore, and you can find the right knob for each job within short time.

Let’s apply the same logic to this song now. First we arrange the chords in groups, or sections. The first group is the intro of the song, and it consists of the first 8 bars. In fact you will find that certain numbers – e.g. 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 32, … – play an important role in music. These are very often powers of two. Indeed music and mathematics are more related than you might think. If you look at these 8 chords, you will see that there is a group of 4 bars (C F Dm G) that is repeated ( 2 x 4 = 8, be aware of the powers of two).

Intro

C F Dm G C F Dm G

Let’s go on and try to identify such groups. After the intro, someting like a chorus begins (“True love will never fade…”). First it is important to understand that the structure of the lyrics has normally to do with the structure of the music, but both are not the same in all details. From the lyrics you might think that the chorus starts when Knopfler sings the first word “True…”, from a musical point of view however, it actually starts with the last word of the line “…fade”). The other words are what is called an upbeat figure, or simply upbeat. They lead over into the next part. A similar upbeat can be found at the beginning of the next part, which starts with the last word of “I wonder if there’s no forever…” at 0:37. Until then, we have a total of the following 10 chords:

Chorus

C F Dm G C F Dm G C C

A closer look reveals that we have the same group of 4 chords as in the intro (C F Dm G) which is repated, plus two bars of a C chord that are something like a filler to connect the part with the next. The 10 bars can be subdivides in 4 + 4 + 2, and we might write it like this instead:

C F Dm G – C F Dm G – C C

The third part – we might call it verse – starts with “…forever” (0:37). As the following part that starts with “I don’t know what brought you to me” sounds almost identical (melody, chords), we can consider it as a repetition of the part before and call it Verse B , while the previous verse A consists of the following 18 chords.

Verse A

F F C C Dm G C C F F C C Dm G F G C C

You can see that the first 8 bars start with the same chords as from bar 9 on, and the last two bars are just a filler to link to the next part, so let’s write it like this:

F F C C Dm G C C – – F F C C Dm G F G – – C C.

And we can subdivide those groups of 8 bars to groups of 4 bars:

F F C C — Dm G C C – – F F C C – – Dm G F G – – C C.

We see that the first and the third group are identical, while the second and the fourth are similar but not the same. The difference are the chords F G (red) at the end of the third group, they are inserted, they change the pattern. If you left them and played the two bars of C instead, you would have a simple repetition which is on the one hand more logical, but on the other hand it sounds a bit surprising this way, and thus adds something new to the song.

The whole section seems to be repeated with the following verse B (1:14 to 1.44) that can be subdivided in a way similar to verse A:

Verse B

F F C C — Dm G C C – – F F C C – – Dm G C

If you compare it to verse A, you will see that both differ just where those chords previously discussed appear (red). Instead of the F G C C we have only one single bar C here. The total number of chords is for this reason only 15 which is very unusual (16 or 16 + 2 would be normal). We can say that one bar of C is missing, Dm G C C would be normal here (and would in fact sound logical). Leaving out this chord breaks the pattern and again adds something unexpected, it highlights the following part by breaking the rules.

This next part might be called bridge. It consists of 8 bars, and it is followed by 4 bars of the chorus pattern, and finally two bars C to fill to the next part, so we have:

Dm G C Am – F G F G (bridge)

C F Dm G (chorus)

C C (fill)

All of the following sections are repetitions of these first parts. In detail, we have the

Solo (first 8 bars of verse A)

Verse B (15 bars)

Bridge (8 bars)

Chorus (4 bars)

3 x Chorus (12 bars)

2 x Chorus (solo, where ride cymbal starts)

C F G

The last chords again break with the pattern. The expected would be something like C F Dm G C, with the last C as the final chord (the song is in the key of C so it should end on a C). The way it is here, however, sounds again unexpected and thus adds something.

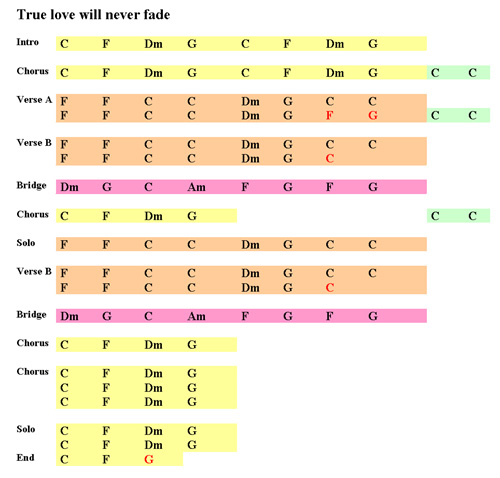

The following chart shows the complete structure of the whole song. I also used different colours to indicate different and related parts. Compared with the unstructered list of 126 chords at the beginning of this article, you can see at one glance which part comes next, where something is repeated, and where something happens that breaks a standard pattern (red chords) . The number of different parts that you need to learn is kept to a minimum.

Some general notes on structure

At all those positions where a new part begins, a traditional note sheet would display a double bar line. Normally a drummer plays a crash cymbal there, and he might play a drum break before to usher in the start of a new part (on this song the drummer does not because the drum track is kept extremely simple). The beginning of a new part is also a typical position where new instruments might come in (e.g. note how the electric guitar comes in at the beginning of the first verse B), and the overall volume of the song might change here (note that commercial CD are often mixed at a rather constant volume as a consequence of the loudness war).

Working with a band

I made the experience that when you work on a song with a band, it is extremely helpful to work with musicians who understand such a concept, and who think in terms of such a structure. Only this way everyone will know e.g. where to start best within the song to practice a particular part of the song, or how to play a difficult piece in a loop to get used to it or to bring it to perfection within shortest time. Everyone will know where to pay attention because something is unusual.

The drummer automatically knows where to play the crash, where to play a break, where to change from hihat to ride, and so on. And only this way you can easily communicate with the other band members: everyone will know what is talked about, what is meant with bridge, first part, second half of … , and so on.

This is common knowledge among good musicians of course, but I know of many who still have not realized these aspects, sometimes even after playing their instruments for decades. But it is never too late for learning 🙂

Note: An analysis of the chords that appear in this song and their harmonic relation can be found in the article about the circle of fifths.