Guitar portrait: 1976 Gibson MK-81 acoustic guitar (Mark series)

With this article, I want to feature my good old acoustic guitar: a Gibson MK-81 from 1976.

I got this guitar more than 20 years ago. I was looking for an acoustic guitar and was trying out all the guitars in that shop. After a while the shop owner brought one more from some room in the back, saying I should try out this one, it was special. This was the Gibson MK-81, and in fact it sounded different from all the other guitars, it sounded more ‘expensive’ in a way, with a warm bass and brilliant treble, like a great HIFI speaker compared with a cheap one. He told me that this guitar had been damaged damage and was not professionally repaired (the bridge had solved from the top and had been glued back to its position, additionally fixed with two screws), and that it normally costs more than 3 times the money I wanted to spend.

Well, we agreed on a deal (I had to part from a nice Tokai Telecaster copy I had back then) and I took this guitar home with me. The damage could be repaired professionally for about 100,- € by the way.

The MK series

I had never heard about these guitars before, and there was not much information available. Remember, this was before the Internet, so you had to look through guitar books at the shop when searching for a particular information. Today it is so much easier. The story behind the Mark series seems to be like this:

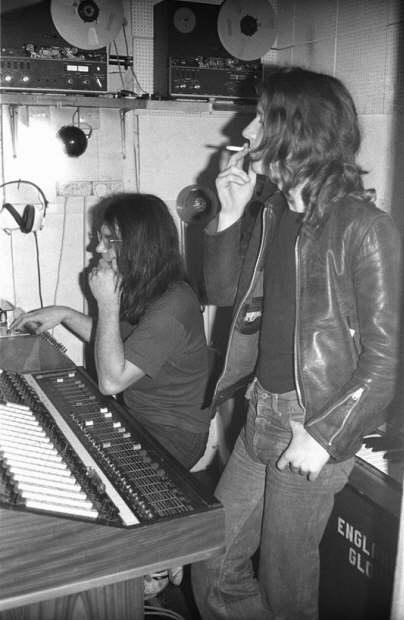

In May of `73 Gibson began the Mark story by contacting Dr. Adrian Houtsma, Professor of Acoustic Physics at MIT, to confirm some research Gibson itself had initiated. Receiving a favorable review, Gibson then went to Dr. Kasha, who was at the time, a chemical physicist working as Director of the Institute of Molecular Biophysics at Florida State University. Combining the findings from Gibson` R&D department and Drs. Houtsma and Kasha, the company finally landed on the doorstep of well known luthier Richard Schneider, who was charged with making the scientific information practical, designing a guitar that fit with Gibson`s aesthetics and capable of being put into production. The Mark series was born…

The Mark series was no commercial success, rather the contrary as it seems. It turned out that science alone was not capable of building perfect guitars made of wood, a material that is unpredictable because each piece of wood has individual features. After only 3 or 4 years Gibson dropped the Mark series again.

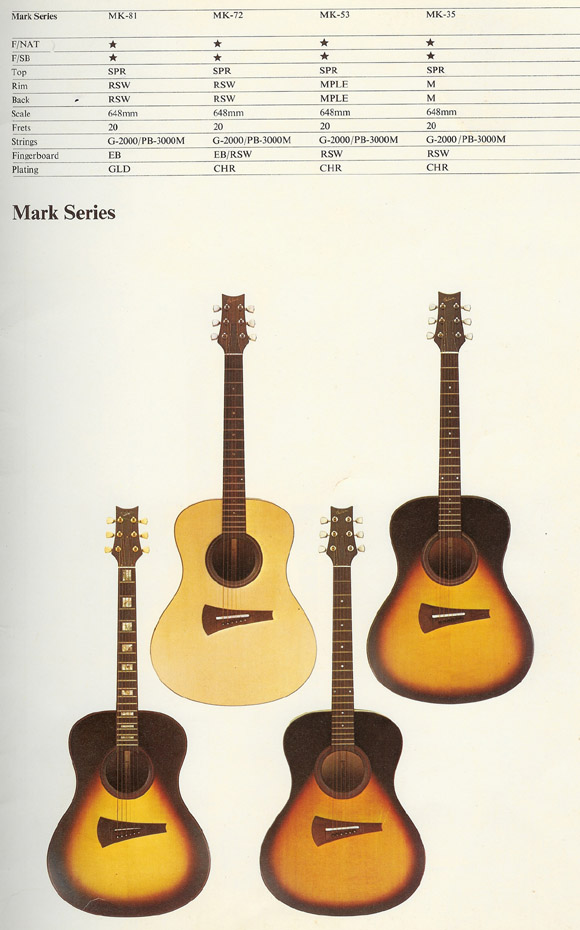

But these guitars were not really bad, and I heard from many owners how much they love their MK’s. The complete series consisted of 5 models, the MK 35, the MK 53, the MK 72, the MK 81, and the MK 99 (the higher the model number, the better the materials, and the higher the price).

Here is a page from a Gibson catalogue from that time that shows the different features of the different models:

The MK-81

Both the rim and back of my MK-81 are made of solid (!) rosewood (possibly Brazilian, but not sure), the top is solid spruce. The neck is curly maple, the fingerboard is ebony with mother-of-pearl inlays. There are some fancy details that make sure that this was the top-model of the production range (in fact, the MK-99 seems to be custom-made by luthier Richard Schneider himself only) like the gold plated hardware or the black and red bindings.

It is a special guitar in fact. It is very deep, and the body and headstock shape looks somewhat unusual. The sound is warm and bright, a bit bell-like. With the heavy Gibson jumbo frets and the “fast” neck shape it plays almost like an electric.

Pictures of my MK 81

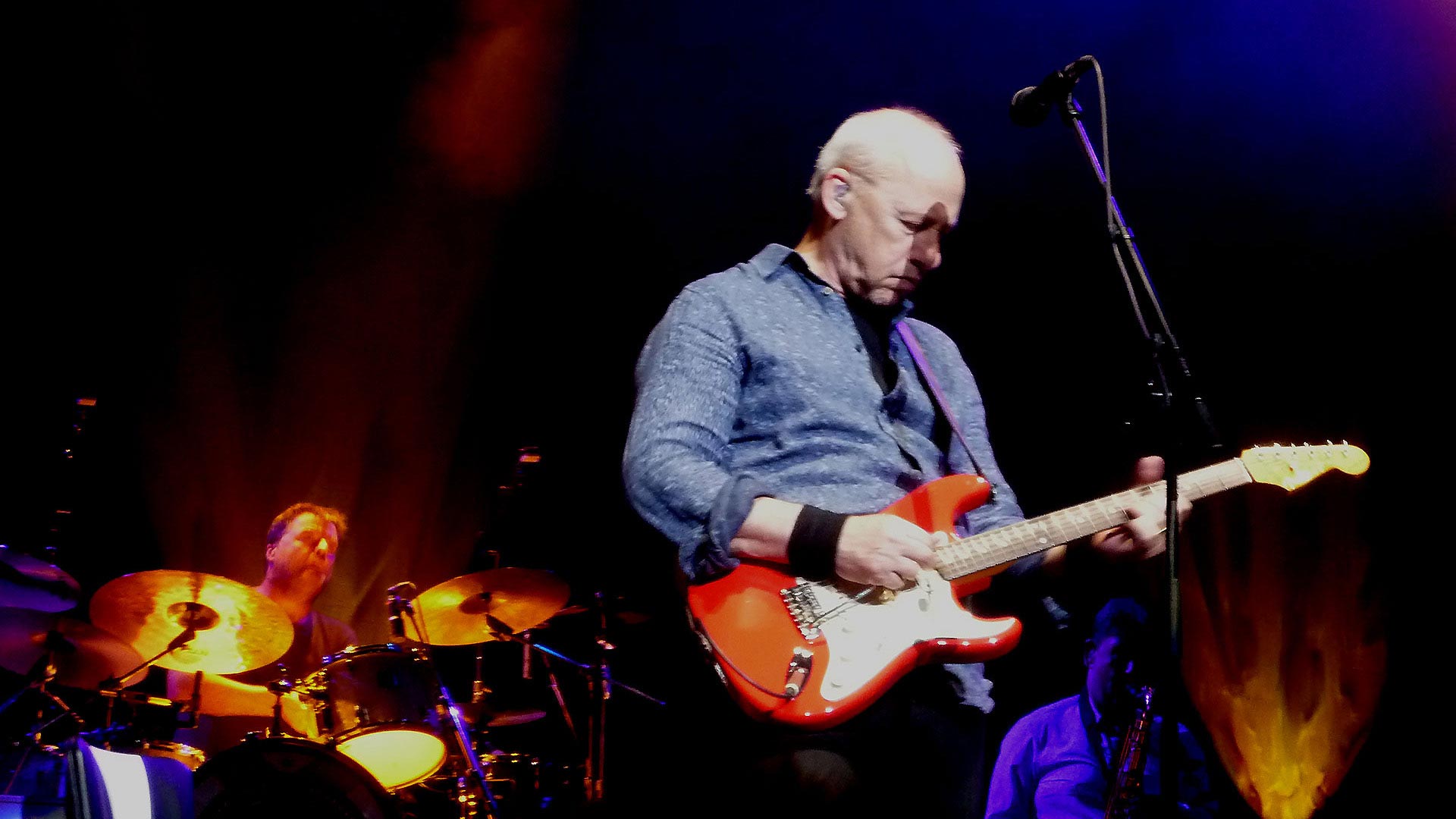

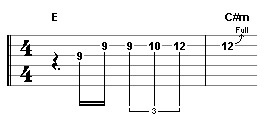

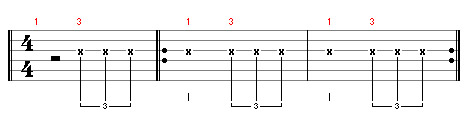

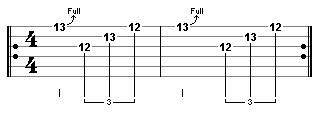

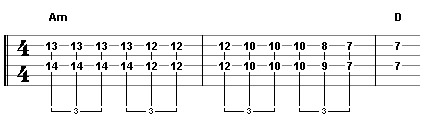

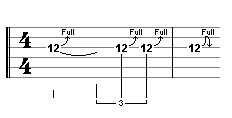

Youtube videos

Two of my latest youtube videos feature this guitar.

If you want the full story and more details of the Mark series, see this article in vintage guitar magazine.